Tags

Abdulbasit Kassim, Black Lives Matter, Cecil Rhodes, Edward Colston, Efunsefan Aniwura, History Wars, Madam Efunroye Tinubu, Oba Adele, Slave Owners in Nigeria, Tinubu Square Lagos

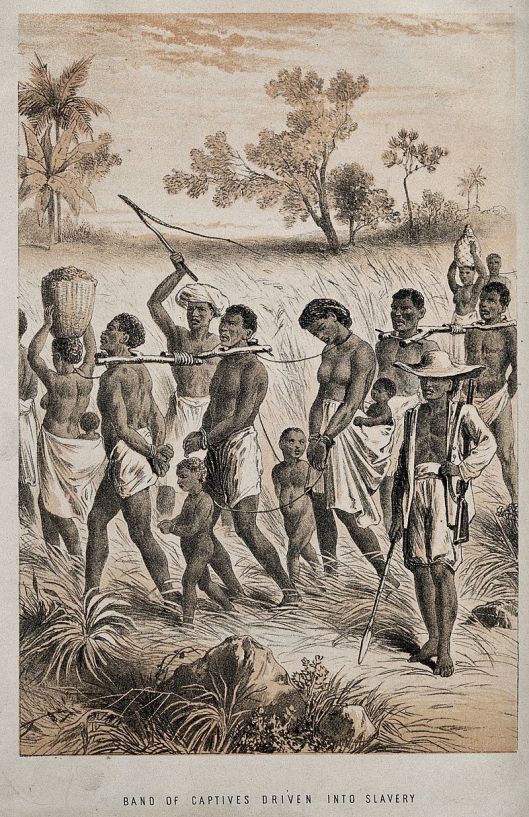

In the light of the ongoing culture wars and Black Lives Matter questioning commemorations of the past, this article by Abdulbasit Kassim, and originally published in “Premium Times” on June 13th as “Edward Colston, History Wars and the legacies of slave owners in Nigeria” is required reading. If you read nothing else on BLM this weekend – read this.

The last paragraph is particularly on point.

Should our society continue to honour the legacies of slaveowners and those who played active roles in the trans-Atlantic and trans-Saharan slave trade? Should our society continue to name monuments, schools, streets, stadiums, and other landmarks after them, even though we are all aware of their dark legacies?… This is about historical accountability and the need to hold people’s legacies to account for the actions they perpetrated in the past.

“One of the great liabilities of history is that all too many people fail to remain awake through great periods of social change” – Martin Luther King

“We live in a moment of history where change is so speeded up that we begin to see the present only when it is already disappearing” – Ronald David Laing

On Sunday, the statue of Edward Colston, the deputy governor of the Royal African Company, was toppled by Black Lives Matter protesters and thrown into the Bristol harbour. Barely 56 hours later, the 150-year-old statue of King Leopold II of Belgium, whose colonisation of and slave holding regime in Congo began in 1885 and led to the deaths of millions, was removed from a public square in Antwerp and deposited at the Middleheim Museum. More than 65,000 people have signed a petition to remove all statues of King Leopold II across Belgium. The removal of the statue of King Leopold II took place two years after the United Nations called on the Belgian government to apologise for the crimes committed during its colonial enterprise and a year after Belgium apologised for the tremendous harm inflicted on Central African nations during its 80 years of their colonisation.

In London, the statue of Robert Milligan, the 18th-century slave trader, who owned two sugar plantations and 526 slaves in Jamaica, was removed from its plinth outside the museum of London Docklands. London’s Mayor Sadiq Khan also announced that more statues of imperialist figures would be removed from the streets of London. The statue of Cecil Rhodes, a Victorian imperialist in southern Africa, whose name fronts Oxford University’s Rhodes scholarship, may also be removed, following the ‘Take it Down – Rhodes Must Fall’ protest. The University of Liverpool also announced that one of its halls of residence named after the former U.K. prime minister, William Gladstone, would be renamed due to his views on slavery and his family connections to slaveholding.

The Plymouth City Council also announced that the public square named after Sir John Hawkins, the Elizabethan seafarer, who is considered to be the first English slave trader to have transported captured Africans to work on plantations in the America in the 16th century, would be renamed because of his role in slave trade.

Edward Colston is gone. Robert Milligan is gone. King Leopold II is gone. Good. Now, let us revisit how the legacies of indigenous slaveowners have been honoured.

According to the British-Nigerian historian, David Olusoga, the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston and other statues is not an attack on history; it is history. Edward Colston was known for his philanthropy and charitable contributions to the city of Bristol. Yet, the previously suppressed dark legacy of his active role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade have surfaced to haunt his memory. The toppling of the statues and relics of colonialism is a domino effect of the global protests in the wake of George Floyd’s death and the call for the removal of Confederate monuments in the U.S., considered by many people as symbols of oppression and racism. Like Edward Colston, the statues of John Castleman in Louisville and Charles Linn in Birmingham and others across the United States have been torn from their plinths and disposed away from public display. The State of Virginia has also initiated the move to remove the huge statue of Confederate General Robert Lee in Richmond, the state capital. The seismic historical change taking place around the world might appear distant and far from Nigeria, however, it should serve as a wake-up call.

There is no better time to revisit how we have honoured the legacies of slaveowners like Madam Efunroye Tinubu, the wife of Oba Adele, who was also one of the ferocious slave dealers who operated the Lagos-Ibadan slavery corridor, delivering slaves for Brazilian and Portuguese export.

What we are witnessing now are “history wars” – the political struggles in which versions of the past – the silenced history – that have long gone largely uncontested are being exposed and challenged. Historical memory is not merely an entity altered by the passage of time; it is the prize in a struggle between rival versions of the past; a question of will, power, and persuasion. The past does not speak for itself, rather actors, institutions, and discourses speak for and shape the meaning of the past through the construction of historical memories. And as with any power struggle, there are actors and interpretations that are winning and those that are not. The previous decades have been times of particularly vigorous public debates about the meanings of the past in many places. More people are beginning to question what has so far been codified as the dominant representations of the past. This is ultimately a battle of ideas, and sooner or later, we will feel the contagious and domino effect here in Nigeria. It is time to revisit the legacies of the slaveowners and those who played active collaborative roles in the trans-Atlantic and trans-Saharan slave trade.

How have we memorialised the legacies of indigenous slaveowners?

There is no better time to revisit how we have honoured the legacies of slaveowners like Madam Efunroye Tinubu, the wife of Oba Adele, who was also one of the ferocious slave dealers who operated the Lagos-Ibadan slavery corridor, delivering slaves for Brazilian and Portuguese export. To demonstrate her commitment to the trade, Madam Tinubu once boasted of drowning her slaves, rather than selling them at a discount. Her statue is honoured and preserved in Tinubu Square on Lagos Island. In his book, Madame Tinubu: Merchant and Kingmaker, Oladipo Yemitan argues that contrary to the projected image of Madam Tinubu as a repentant slave trader, who fought against slave trade, she secretly continued trading in slaves until her death in 1887. Madam Tinubu was not alone. Efunsetan Aniwura was probably the most ruthless of all the slave dealers in South-West Nigeria. She was an extremely wicked slave dealer. This woman made it an abomination for her female slaves to get pregnant, and when they did, she openly beheaded them in cold blood at the Ibadan Town Square.

How exactly is the crime of Edward Colston and Robert Milligan different from the legacies of Madam Tinubu and Efunsetan Aniwura? Why should Edward and Robert be dishonoured abroad, while we continue to honour Efunsetan and Madam Tinubu at home? People still honour and revere the legacies of Oba Akintoye, Kosoko, Ologun Kutere, Akinsemoyin and others, who were the biggest slave traders in Lagos. How exactly are they different from Edward Colston and Robert Milligan? It is even on record that Oba Kosoko bought Nigerian slaves who were previously sold and transported to Bahia, because he needed their skills to build Brazilian type houses and produce European items in Lagos. Oshodi Tapa, Dada Antonio, Ojo Akanbi and others who were former slaves and later became big time slave merchants themselves built generational wealth from the slave trade that survives till present. Today, the legacies of these slaveowners are not only revered and whitewashed, but their children are still benefiting from the wealth their ancestors passed down from slavery. These are examples from the South.

In Northern Nigeria, there are too many examples to cite. According to some estimates, by the late 19th century, slaves constituted about 50 per cent of the population of the emirate in Adamawa. The Lamido of Adamawa received an estimated 5,000 slaves in tributes annually, in addition to those captured during the expeditions conducted by his brothers. As Chinedu Ubah explains in his article on the suppression of slave trade in the Nigerian emirates, the emirate of Adamawa was among the last emirates in northern Nigeria to abandon the traffic in slaves. Even after the abolition of slave trade, Catherine Vereecke argues in her research on slave trade in Adamawa that linguistic markers that differentiate the rimdinabe (freed slaves) and their descendants from the rimbe (free persons and true Fulbe) are still prevalent in Adamawa till date.

…Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani emphasised the need for Africans to reckon with the complicated legacy our ancestors played in the slave trade. This act of reckoning should usher a moment for posing questions of historical guilt and a culture of apology for the injustices perpetrated against fellow Africans…

Although ex-slaves and their descendants have immersed themselves in the Fulbe society, they have not been able to fully escape their marginal slave status. Indeed, some ‘true Fulbe’ still take pride in the legacies of their ancestors as slaveowners and others still hold the belief that slave lands belongs to the ‘Fulbe’ by the right of conquest. Those ‘true Fulbe’ who take pride in the slave-raiding of their ancestors are not different from the Brits defending the slave legacies of Cecil Rhodes, Edward Colston and Winston Churchill in England. Beyond Adamawa, virtually all the emirates in Northern Nigeria were once bastions of slave dealers, with emirs who serially abused young girls and religiously justified their sexual enslavement under the guise of “concubinage”. The cruelty of slavery in northern Nigeria is documented in the book The Diary of Hamman Yaji: Chronicle of A West African Muslim Ruler, edited by James Vaughan and Anthony Kirk-Greene. Sean Stilwell and Heidi Nast also wrote excellent books on the noxious enslavement and concubinage that took place across the emirates in northern Nigeria, such as in Paradoxes of Power: The Kano Mamluks and Male Royal Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate 1804-1903 and Concubines and Power: Five Hundred Years in a Northern Nigerian Palace.

This is not a regional issue. From the North to the South, there are people who were complicit in the same crimes perpetrated by Edward Colston and Robert Milligan but whose legacies are still revered and honoured. In fact, we should look at Port Harcourt city. The city is named after Lewis Vernon Harcourt, the British secretary of state, who was also a sex maniac. Lewis Harcourt was a serial child abuser and he abused both young boys and girls. Today, the hub of the oil industry in Nigeria is named after him. Some of our streets are named after colonial officers and local slave warriors with very dark histories. One of the most popular streets in Ikoyi is named after Algernon Willoughby Osborne, who was a British official responsible for the administration of colonial law in Southern Nigeria. In his book, Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901-1914, Jeffrey Green writes about how Algernon Osborne and his wife Mary Osborne treated their Gambian slave girl. Algernon Osborne did not only display racist character during his wife’s court case with the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) at St. Albans in September 1908, he also held the belief that “the only way to correct black people was to flog them.” Today, a major road is named in his honour.

The questions here are: Should our society continue to honour the legacies of slaveowners and those who played active roles in the trans-Atlantic and trans-Saharan slave trade? Should our society continue to name monuments, schools, streets, stadiums, and other landmarks after them, even though we are all aware of their dark legacies? What would this official recognition say about how we honour certain versions of the past? Should we just forget and overlook this? Or should we follow the Donald Duke approach and build a slave museum to document the dark histories? Some people might argue that: Why are we speaking about this history now? What exactly is the goal? Is this driven by the penchant to mimic the current trend of protests across Western capitals? Or are we revisiting this history to re-traumatise or stir up ethnic hatred? This is not about the West or the East. This is about historical accountability and the need to hold people’s legacies to account for the actions they perpetrated in the past.

In her Wall Street Journal article “When the Slave Traders Were Africans”, Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani emphasised the need for Africans to reckon with the complicated legacy our ancestors played in the slave trade. This act of reckoning should usher a moment for posing questions of historical guilt and a culture of apology for the injustices perpetrated against fellow Africans, whose ancestors were killed and whose lineages were disrupted by the business of slave trade. The Europeans could not have gone into the interior themselves, they had to rely on African merchants and middlemen who traded their fellow Africans as slaves. Those middlemen like Efunsetan and Madam Tinubu and others who participated in the trans-Atlantic and trans-Saharan slave trade also deserve to be held accountable. I hope that when this seismic historical change manifests itself in Nigeria, the descendants of slaveowners in Nigeria would be brave enough to act and speak like Robert Wright Lee (the descendant of Robert Lee): “We have a chance here today…to say this will indeed not be our final moment and our final stand. This statue of my ancestor is a symbol of oppression and I support its removal.”

Abdulbasit Kassim is a PhD Candidate in Islam and Africana Studies at Rice University and a Visiting Doctoral Fellow at the Institute for the Study of Islamic Thought in Africa at Northwestern University. @scholarakassi1

Image credit: Wikipedia

Copyright David Macadam 2020